Rebooked

Tuesday | March 15, 2011 open printable version

open printable version

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (Frank Tashlin, CinemaScope).

DB here:

Are blog readers book readers, let alone book buyers? I asked once before, but in a different tone of voice. Books are still being published, thick and fast, and everybody who cares about cinema should take a look at these.

In the frame

Ballet mécanique.

When the talk turns to the great film theorists of the heroic era, you hear a lot about Bazin and Eisenstein, less about Rudolf Arnheim. But the prodigiously learned Arnheim pioneered the study of art from the perspective of Gestalt psychology. Although he’s probably best known for his studies of painting in Art and Visual Perception, as a young man he was a film critic and in 1930 published a major theoretical book on cinema. First known in English as Film, then in its 1957 revision as Film as Art, this has long been considered a milestone. But Arnheim was famously skeptical of color and sound movies, and he had comparatively little to say about the many cinematic trends after 1930. (He died in 2007, aged 102.) While psychologists grew wary of Gestalt ideas, cinephiles embraced Bazin and academics moved toward semiotics and other large-scale theories. For some time Arnheim has seemed a graceful, erudite relic.

A new anthology seems likely to change that view. Arnheim for Film and Media Studies, edited by Scott Higgins, reveals one of the earliest and most energetic and pluralistic thinkers about modern media. The fourteen authors probe Arnheim’s ideas about film, of course–showing unexpected connections to the Frankfurt School and to avant-gardists like Maya Deren. But there are as well essays on Arnheim’s thinking on photography, television, and radio, along with studies that examine how his ideas would apply to comic books and digital media. Other contributors provide conceptual reconstructions, analyzing his ideas on composition and stylistic history.

A new anthology seems likely to change that view. Arnheim for Film and Media Studies, edited by Scott Higgins, reveals one of the earliest and most energetic and pluralistic thinkers about modern media. The fourteen authors probe Arnheim’s ideas about film, of course–showing unexpected connections to the Frankfurt School and to avant-gardists like Maya Deren. But there are as well essays on Arnheim’s thinking on photography, television, and radio, along with studies that examine how his ideas would apply to comic books and digital media. Other contributors provide conceptual reconstructions, analyzing his ideas on composition and stylistic history.

This is no esoteric exercise. The essays present probing arguments with patient lucidity. Encouragingly, most of the contributors are early in their careers. (I have a piece in the collection as well, an expanded version of a blog entry.) The anthology proves that a seminal thinker can always be reappraised. There’s always more to be understood.

In the Higgins collection Malcolm Turvey furnishes an essay on Arnheim’s relation to various strands of modernism. That vast movement is treated at greater length in Turvey’s new book, The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s. At the book’s core are close analyses of five exemplary films encapsulating various trends. Turvey studies Richter’s Rhythm 21 and abstract film, Léger and Murphy’s Ballet mécanique and cinéma pur, Clair’s Paris Qui Dort and Dada, Dalí and Buñuel’s Chien Andalou and Surrealism, and Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera and the “city symphony” format. For each film Turvey provides informative historical background and, often, some controversial arguments. For example, he finds Léger to be surprisingly concerned with preserving classical standards of beauty. Indeed, one overall thrust of the book is to suggest that modernism was less a rejection of all that went before than a selective assimilation of valuable bits of tradition. (This applies as well to Eisenstein, I think, as I try to show in my book on his work.)

No less controversial is Turvey’s careful dissection of what has come to be known as “the modernity thesis.” This is the idea that urbanization, technological change, and other forces have fundamentally changed the way we perceive the world, perhaps even altered our basic sensory processes. Specifically, some argue, because the modern environment triggers a fragmentary, distracted experience, that experience is mimicked by certain types of film, or indeed by all films. Step by step Turvey argues that this is an implausible conclusion. This last chapter is sure to stir debate among the many scholars who argue for film’s essential tie to a modern mode of perception.

Harper Cosssar’s Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema begins in the heyday of Arnheim and the silent avant-garde. Indeed, some of the early uses of widescreen, as in Gance’s Napoleon, are indebted to experimental film. But Cossar’s genealogy of widescreen also mentions horizontal masking in Griffith films like Broken Blossoms and lateral or stacked sets in Keaton comedies like The High Sign. More fundamentally, Cossar develops Charles Barr’s suggestion that the sort of viewing skills demanded by widescreen (at least in its most ambitious forms) were anticipated by directors who coaxed viewers to scan the 4:3 frame for a variety of information. The “widescreen aesthetic” was implicit in the old format, and technology eventually caught up to allow it full expression.

Harper Cosssar’s Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema begins in the heyday of Arnheim and the silent avant-garde. Indeed, some of the early uses of widescreen, as in Gance’s Napoleon, are indebted to experimental film. But Cossar’s genealogy of widescreen also mentions horizontal masking in Griffith films like Broken Blossoms and lateral or stacked sets in Keaton comedies like The High Sign. More fundamentally, Cossar develops Charles Barr’s suggestion that the sort of viewing skills demanded by widescreen (at least in its most ambitious forms) were anticipated by directors who coaxed viewers to scan the 4:3 frame for a variety of information. The “widescreen aesthetic” was implicit in the old format, and technology eventually caught up to allow it full expression.

Cossar advances to more familiar ground, studying early widescreen practice in The Big Trail and moving to analyses of films by masters like Preminger, Ray, Sirk, and Tashlin. Although most chroniclers of the tradition stop in the early 1960s, Cossar presses on to consider the changes wrought by split-screen films like The Boston Strangler and The Thomas Crown Affair. The survey concludes with discussions of cropping techniques in digital animation (e.g., Pixar) and web videos, which often employ letterboxing as a compositional device. In all, Letterbox traces recurring technological problems and aesthetic solutions across a wide swath of film history.

Critics’ corner

Two of America’s senior film writers have revisited their earlier writings, with lively results. Dave Kehr’s collection When Movies Mattered samples his Chicago Reader period, from 1974 to 1986. Disguised as weekly reviews, Kehr’s pieces were nuanced essays on films both contemporary and classic.

Turn to any of them and you will find a relaxed intelligence and a deep familiarity with film history. By chance I open to his essay on Billy Wilder’s Fedora:

Turn to any of them and you will find a relaxed intelligence and a deep familiarity with film history. By chance I open to his essay on Billy Wilder’s Fedora:

It resurrects the flashback structure of his 1950 Sunset Boulevard, but it goes further, placing flashbacks with flashbacks and complicating the time scheme in a manner reminiscent of such demented 40s films noirs as Michael Curtiz’s Passage to Marseille and John Brahm’s The Locket. . . But the jumble of tenses also clarifies the film’s design as a subjective stream of consciousness. The images come floating up, appearing in the order of memory.

How many of those reviewers whose flash-fried opinions count for so much on Rotten Tomatoes can summon up information about the construction of Passage to Marseille or The Locket? And how many could make the case that Wilder, in returning to the forms fashionable in his early career, would repurpose them for the sake of a reflection on death, resulting in “a film as deeply flawed as it is deeply felt”? Kehr’s work from this period is appreciative criticism at its best, and he never lets his knowledge block his immediate response. “I admire Fedora, but it also frightens me.” It’s time we admitted that Dave Kehr, working far from both LA and Manhattan, was writing some of the most intellectually substantial film criticism we have ever had.

Also hailing from the Midwest is Joseph McBride, a professor, critic, and biographer. Apart from his rumination on Welles, his books have focused on popular, even populist, directors like Capra (The Catastrophe of Success), Ford (Searching for John Ford), and Spielberg (Steven Spielberg: A Biography). The University Press of Mississippi and bringing first two volumes of this trilogy back into print, and it has just reissued the third in an updated edition.

Here Spielberg emerges as far more than a purveyor of popcorn movies. McBride sees him as a restless, wide-ranging artist, and the additions to the original book have enhanced his case. McBride offers persuasive accounts of Amistad and A.I., which he regards as major achievements. He goes on to argue that Spielberg’s unique power in the industry allowed him to face up to central political issues of the 2000s.

He made a series of films in various genres reflecting and examining the traumatic effects of the September 11, 2001, attacks and the repression of civil liberties in the United States during the George W. Bush/ Dick Cheney regime. . . . No other major American artist confronted the key events of the first decade of the century with such sustained and ambitious treatment (450).

McBride is no cheerleader. He can be as severe on Spielberg’s conduct as on his films, criticizing much of the DreamWorks product as dross and suggesting that Spielberg sometimes trims his sails in interviews. I’d contend that McBride underrates some of Spielberg’s work, notably Catch Me If You Can and The War of the Worlds. But McBride has perfected his own brand of critical biography, blending personal information (he reads the films as autobiographical), tendencies within the film industry and the broader culture, and critical assessment. All studies of Spielberg’s work must start with McBride’s monumental book. Ten years from now we can look forward to another update; surely his subject will have made a few more movies by then.

Foreign accents

8 1/2.

Today we regard Citizen Kane as a classic, if not the classic. But for several years after its 1941 release it wasn’t considered that great. It missed a place on the Sight and Sound ten-best critics’ polls for 1952; not until 1962 did it earn a spot (though at the top). Its rise in esteem was due to changes in film culture and, some have speculated, the fact that Kane was a regular on TV during the 1960s. Something similar happened with His Girl Friday, another stealth classic. I’ve traced what I know about its entry into the canon in an earlier blog entry.

What about the postwar classics like Open City and Bicycle Thieves and the works of Bergman and Fellini and Antonioni and Kurosawa and the New Wave? Surely some of the films’ fame comes from their intrinsic quality—many are remarkable movies—but would we regard them the same way if their reputation hadn’t spread so widely abroad, especially in America? Questions like this lead us to what film scholars have come to call canon formation: the ways artworks come to wide notice, receive critical acclaim, and eventually become taken for granted as classics.

Consider this. The Toronto International Film Festival’s recent list of 100 essential films includes thirty non-Hollywood titles from the 1946-1973 period, more than from any comparable span. Of the TIFF top twenty-five, twelve are from that era. You can argue that these years, during which several generations of viewers overlapped, set in place a system of taste that persists to this day.

Consider this. The Toronto International Film Festival’s recent list of 100 essential films includes thirty non-Hollywood titles from the 1946-1973 period, more than from any comparable span. Of the TIFF top twenty-five, twelve are from that era. You can argue that these years, during which several generations of viewers overlapped, set in place a system of taste that persists to this day.

Tino Balio’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 reveals a side of canon formation that’s too often overlooked. Balio is less concerned with analyzing films than Turvey, Cossar, Kehr, and McBride are. He is asking a business question: What led the U. S. film industry to accept and eventually embrace films so fundamentally different from the Hollywood product?

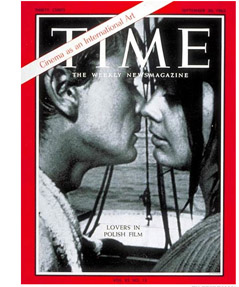

Several researchers have pointed to the roles played by influential critics, film festivals, and new periodicals like Film Comment and Film Culture. Intellectual and middlebrow magazines promoted the cosmopolitan appeal of the foreign imports. By 1963 Time could run a feverish cover story on “The Religion of Film” to coincide with the first New York Film Festival.

Balio duly notes the importance of such gatekeepers and agenda setters. But he goes back to the beginnings, with the small import market of the 1930s. Turning to the prime postwar phase, he broadens the cast of players to include the business people who risked buying, distributing, and publicizing movies that might seem hopelessly out of step with US audiences. He shows how small importers brought in Italian films at the end of the 1940s, and these attracted New York tastemakers, notably Times critic Bosley Crowther, who were keen on social realism. Within a few years ambitious entrepreneurs were marketing British comedies, Swedish psychodramas, Brigitte Bardot vehicles, and eventually the New Waves and Young Cinemas of the 1960s. As distributors fought censors and slipped films into East Side Manhattan venues, an audience came forward. The “foreign films”—often recut, sometimes dubbed, usually promoted for shock, sentiment, and sex—were positioned for the emerging tastes of young people in cities and college towns.

Balio offers fascinating case studies of how the films were handled well or badly. Kurosawa, he notes, had no consistent distributor in the US, and so his films gained comparatively little traction. By contrast there was what one chapter calls “Ingmar Bergman: The Brand.”

Balio offers fascinating case studies of how the films were handled well or badly. Kurosawa, he notes, had no consistent distributor in the US, and so his films gained comparatively little traction. By contrast there was what one chapter calls “Ingmar Bergman: The Brand.”

Bryant Haliday and Cy Harvey of Janus Films. . . devised a successful campaign to craft an image of Bergman as auteur and to carefully control the timing of each release. . . . Janus released the films in an orderly fashion to prevent a glut on the market and to milk every last dollar out of the box office. No other auteur received such treatment.

The work paid off: Bergman made the cover of Time in 1960, and soon The Virgin Spring and Through a Glass Darkly won back-to-back Oscars for Best Foreign Language Film. Eventually, Bergman and other foreign auteurs attracted the big studios. Now that small distributors had shown that there was money in coterie movies, the major companies (having problems of their own) embraced imported cinema—first through distribution and eventually through financing. If you admire Godard’s The Married Woman, Band of Outsiders, and Masculine Feminine you owe a debt to Columbia Pictures, which underwrote them.

Work like Balio’s does more than bring the name Cy Harvey into film history. It reminds us to follow the money. If we do, we’ll see that not every “foreign film” stands radically apart from big bad Hollywood. More generally, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens reminds us that even high-art cinema is produced, packaged, and circulated in an economic system. The distinction between commercial films and personal films, business versus art, is a wobbly one. Rembrandt painted on commission and Mozart was hired to write The Magic Flute. Sometimes good art is good business.

I couldn’t work this in anywhere else: The bulk of the essays in Arnheim for Film and Media Studies are by people associated with our department at Wisconsin. They do us proud, naturally. Incidentally, Joe McBride went to school at UW too, and Tino and I taught together here for over thirty years.

Dave Kehr maintains a blog and teeming forum here.

Hart Perez has made a documentary, Behind the Curtain: Joseph McBride on Writing Film History. An excerpt is here. McBride’s website has information about his many projects.

James E. Cutting provides an unusually precise account of canon creation in his 2006 book Impressionism and Its Canon, available for free download here. I’ve written an earlier blog entry discussing Jim’s research into film.

My mention of American generations is based on Elwood Carlson’s study The Lucky Few: Between the Greatest Generation and the Baby Boom. Carlson examines the varying experiences and life chances of people who fought in World War II; people who came of age during the 1960s; and the less populated cohort that fell in between. Doing some pop sociology, I’d hypothesize that the art-film market’s growth relied on a convergence of all three, which were more disposed to art film than cohorts in earlier periods. For example, veterans who had served overseas and gone to college on the GI Bill were more familiar with non-US cultures than their parents and, I surmise, weren’t entirely put off by foreign films. When I first met Kristin’s mother, Jean Thompson, she already knew the work of Carl Dreyer, having seen Day of Wrath at an art cinema in Iowa City. She was in graduate school after World War II, on the G.I. Bill, as was her new husband, Roger, also in school on the G.I. Bill and managing that art cinema. They saw Children of Paradise and other wartime foreign films just getting their releases in the U.S., as well as post-war films like Bicycle Thieves.

The Lucky Few, also known as the Good Times generation, were born between the late twenties and the early 1940s. They were well placed to enjoy postwar prosperity and the period’s explosion of artistic expression. The Lucky Few cohort includes powerful film critics like John Simon (born 1925), Andrew Sarris (1928), Richard Roud (1929), Eugene Archer (1931), Susan Sontag and Richard Schickel (1933), and Molly Haskell (1939). Aged between twenty and thirty when the foreign-film wave struck, they were mighty susceptible to it. (Pauline Kael, though born in 1919, had a delayed career start, entering film journalism in the 1950s along with Sarris et al.) You might slip in David Thomson (born 1941), Jonathan Rosenbaum (1943), and Richard Corliss (1944).

The Baby Boomers jumped on the carousel in the 1960s, with results that are all too apparent. Dave Kehr and Joe McBride are Boomers, as are Kristin and I. Tino, for the record, is ageless.

Minority Report.